SONS OF DEWITT COLONY TEXAS

© 1997-2008, Wallace L. McKeehan, All Rights Reserved

Nathan Boone

Burket-Index | David Burket Family

Early Days in Texas by Nathan Boone Burkett

(1820-1898)

An unfinished manuscript dictated at

Moulton, Lavaca County, Texas in April 1895 to son-in-law John T. Hogwood. Scanned and

transcribed May 1997 by second great grandnephew Wallace L.

McKeehan from the original Hogwood typescript from the collections in The Center for American History, University

of Texas Austin. Topical headings with links are those added by WLM in addition to

bracketed editorial comments. A letter home, reprinted below,

while serving in the CSA at Los Indios in 1865 gives additional insight into uncle Nate

Burkett.

An unfinished manuscript dictated at

Moulton, Lavaca County, Texas in April 1895 to son-in-law John T. Hogwood. Scanned and

transcribed May 1997 by second great grandnephew Wallace L.

McKeehan from the original Hogwood typescript from the collections in The Center for American History, University

of Texas Austin. Topical headings with links are those added by WLM in addition to

bracketed editorial comments. A letter home, reprinted below,

while serving in the CSA at Los Indios in 1865 gives additional insight into uncle Nate

Burkett.

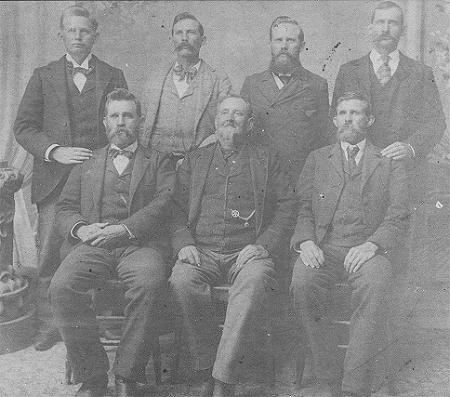

Photo: Nathaniel Boone Burkett (lower center) and sons from left to right, Robert E. Lee, Joseph Benjamin, Samuel Scott, Jacob Coonts, John Elisha and Thomas Judson, ca. 1890. An enlargement of the photo indicates that uncle Nate's watchchain consists of his Texas Ranger star and probably a Masonic or other fraternal icon.

From Missouri to the Lavaca Bay. I was born on October 20, 1820, seven miles north of Jefferson City, Missouri, near a small stream which was then known as Cedar Creek. My parents on both sides were early settlers of Missouri and my father, David Burket, was a close friend of the Boone family. In fact I was named for the oldest son of Daniel Boone, and must have acquired much of his love for hunting and the great outdoors.

[Nathan Boone, b. 2 Mar 1781, m. Olive Van Bibber, was actually the youngest son of Daniel and Rebecca Bryan Boone. The Burkets and Zumwalts came to the St. Charles District of Missouri about the same time, knew each other well during development of the area and served together in numerous actions in protecting the settlements from Indian attacks--WLM].

My father was of sturdy Pennsylvania stock and possessed all the hardy qualities that were needed to make a real pioneer. Hearing about the many advantages the province of Texas offered, he brought his family and came with other settlers in a group that was to compose a portion of Green DeWitt's Colony. Most of the trip was made by traveling by water, coming by way of New Orleans. We landed at the mouth of the Lavaca River on the coast of South Texas on June 16, 1829. Being nine years old at the time I can distinctly remember the first persons we saw at the landing were ten or twelve friendly Indians. They came on board the schooner as if to welcome us, and to help unload our goods and supplies.

[Uncle Nate probably was off by one year meaning 1830 when he would be nine years old having been born in Oct 1820. His father and grandparents appeared in person in CallawayCo in Mar 1830 to complete a land transaction--WLM].

The section of the coast where we landed was level prairie, and one could see for a considerable distance. We soon sighted hundreds of deer and other wild animals. That section was practically uninhabited at the time and there was game and wild life in abundance. We were soon met at the landing by one of the few settlers living near there, who came with his ox-wagon and hauled us out to his cabin, where we stayed for four or five days. Then a wagon train of some six in number came from Gonzales to haul us and our supplies to the colony, which was about ninety miles to the northwest. This trip inland to the Gonzales settlement required four or five days, the roads being just slightly used trails, and traveling in wagons drawn by oxen was rather difficult and slow.

There were five families in our group, all being friends and neighbors from the same section of Missouri, which was also the home state of Green DeWitt. We went to the headquarters of DeWitt's Colony, which was located at the Gonzales settlement, on the Guadalupe River, and the head of each family was assigned land in that colony. Our family remained there for about six years, when the invading army of Santa Anna in early 1836 caused these early settlers to remove their families farther east. This departure from Gonzales and other Texas settlements towards the Louisiana border is often referred to as "The Run-Away Scrape," and was really one of the most critical times of early day Texas. In the year 1838, after Texas had become a republic, we returned to DeWitt’s Colony, and this time made our home about sixteen miles south of Gonzales along some high bluffs overlooking the Guadalupe River.

[The Burkets returned to property on the Gonzales-DeWitt County line on a tract on Boggy Creek of which at least a mile fronted on the Guadalupe River. The tract was on a quarter sitio originally granted to Jesse McCoy, a member of the Gonzales Alamo Relief Force and casualty of the Alamo-WLM].

At the time of writing this story relating these past events and personal happenings, I am living in Lavaca County near Old Moulton, which is in the northeast corner of the county near the Gonzales county line. I have been living here for forty-two years, this tenth day of January, 1895. (Green DeWitt's old records show this tract was "titled" to David Burket, May 10, 1832 and that another small tract later used for the Gonzales Fair Grounds, was passed for title November 26, 1831)

Meeting Sam Houston. I have been asked many times whether I ever met Sam Houston or had any personal dealings with him. I saw him on different occasions and heard him speak several times at and near Gonzales, and I remember meeting him under one peculiar circumstance. I was with five or six young fellows at Gonzales one fine holiday, and one of them got on a "high lonesome'' and roped the "Big Chief" Sam Houston. He said "Boys, don't tear my fine clothes; they cost a lot of money." And then he asked us what we would like to have as a treat. We told him we would like to have a supply of apples and candy, as we had already taken on too many drinks. He complied with our request, and we want on our way rejoicing. The next time I saw Sam Houston was at Washington-on-the Brazos; he was hugging a big Indian Chief and saying "Big Bob-a-chella, Me Sam Houston." I also saw General Houston at other times when he was for the second time President of the Texas Republic, and some years afterward when he was governor of the state of Texas.

With Capt. Cameron at Lipantitlan on the Nueces River. During the early part of 1842 I was with a scouting party that made a trip down on the Nueces River about thirty or forty miles above Corpus Christi. We camped close to a company of volunteers from Mississippi, who were under the charge of Jefferson Davis [Gen. James Davis], and had come to the frontier to help Texas out of her troubles. Late in the evening we received word that we would be attacked before daylight the next morning; and so we were by about seven hundred Mexicans. Our little force all counted numbered only one hundred and thirty men. The enemy had a six pound cannon, which they played over us with grape and canister shot, but did no damage except to wound one man in the head with a small ball. We had taken our position between a deep ravine and the Nueces River, which formed a V and we were backed by a heavy timbered bottom. The evening before General Jeff Davis had planned to change the position of his camp, but during the night apparently decided to return to his former location, He started back to his old camp at daybreak and got about half way when the Mexicans began to fire on that site. He gave the command: "Halt, Fall in; Fall in." Captain Ewing Cameron upon hearing him said: "Boys, one of you run up and tell Davis to fall back to the gully, or they will whip h--- out of him in about two minutes out there in the prairie." About that time the Mexicans blew a charge, and their men started to advance towards us through a very thick fog but they were unable to run their men on up to our location because we had the advantage of them on account of the thick brush. When they had advanced to within one hundred and thirty yards of us, I killed the first Mexican, and my friend on the left said: "What the h--- did you shoot so quick for?" I then told him they had come close enough to suit me, and that I had a dead bead on him. He then said: "Well, you got him down, and I guess you stopped that one." Some of our men finally located the leader of the Mexican advance, who turned out to be an engineer in charge of surveying work for the Mexican government. Some of our sharpshooters crawled up the gully and shot the engineer, killing him instantly and thus ended the fight. It later developed that this engineer was a Spaniard with fair hair and blue eyes. We got five of the Mexicans that we know of, and had some of our men slightly wounded; however, we helped keep the Mexicans from claiming again the territory on this side of the Rio Grande.

This incident or

incidents above appear to be part of the several scouting expeditions carried out by Capt.

Ewen Cameron and his "cowboys" and Capt. John Price and company culminating with

the confrontation with the Mexican troops of General Canales on the Nueces River at

Lipantitlan in early June 1842. These actions were in response to incursions of the

Mexican Army into Texas in which President Houston moved the capital from Austin to

Houston. He issued urgent appeals to the United States for aid to prepare for an invasion

of Mexico. In response came General James Davis (left) who was to command and drill

volunteers. According to John Henry Brown in History of Texas, General Davis had abandoned

his main campsite, but left tents in place. Gen. Canales with a force of about 700 made a

attack without response on the tents. Discovering Davis' actual position advancing toward

the camp in a ravine, Canales attacked, but was repelled by the fire of Capt. Cameron's

company and other Texans. After the leader of a platoon of about fifty men was killed as

described above, Gen. Canales' forces withdrew. The force under Gen. Davis was soon after

disbanded. Uncle Nate's recollection of the event is similar to that of in an unidentified soldier's letter to a friend in Ohio.

The official Mexican version of the encounter, which is described as a glorious victory

having specific benefits which were enumerated, was reported by Gen. Canales in his report to superior Gen. Isidro Reyes.

Canales reported 3 of his men killed, 1 mortally wounded and 1 wounded---WLM.

This incident or

incidents above appear to be part of the several scouting expeditions carried out by Capt.

Ewen Cameron and his "cowboys" and Capt. John Price and company culminating with

the confrontation with the Mexican troops of General Canales on the Nueces River at

Lipantitlan in early June 1842. These actions were in response to incursions of the

Mexican Army into Texas in which President Houston moved the capital from Austin to

Houston. He issued urgent appeals to the United States for aid to prepare for an invasion

of Mexico. In response came General James Davis (left) who was to command and drill

volunteers. According to John Henry Brown in History of Texas, General Davis had abandoned

his main campsite, but left tents in place. Gen. Canales with a force of about 700 made a

attack without response on the tents. Discovering Davis' actual position advancing toward

the camp in a ravine, Canales attacked, but was repelled by the fire of Capt. Cameron's

company and other Texans. After the leader of a platoon of about fifty men was killed as

described above, Gen. Canales' forces withdrew. The force under Gen. Davis was soon after

disbanded. Uncle Nate's recollection of the event is similar to that of in an unidentified soldier's letter to a friend in Ohio.

The official Mexican version of the encounter, which is described as a glorious victory

having specific benefits which were enumerated, was reported by Gen. Canales in his report to superior Gen. Isidro Reyes.

Canales reported 3 of his men killed, 1 mortally wounded and 1 wounded---WLM.

Fighting Gen. Woll and the Battle of Salado. We then made our way to Victoria, and went for three days without anything to eat except some boiled garfish in clear water, and only one mess of that. After reaching the town of Victoria, I left Captain Cameron and his company, as I felt it my duty to return home near Gonzales, some sixty miles up the Guadalupe River to the north. I had been at home for the short period of ten days when the report came in that the Mexicans had returned to San Antonio and captured it. Captain Cameron came up from Victoria to my home and said "Burkett, are you going with us?" I replied that I certainly was. I mounted my horse and went to Gonzales the next day. There I found Captain Caldwell, Ben and Henry McCulloch organizing a company to meet the Mexicans who had taken San Antonio. I was personally acquainted with the McCulloughs and had been with them in a good many Indian fights, and had also been with "Old Paint" Caldwell on some of his campaigns. After getting together about one hundred men we started towards San Antonio. Our number increased until we reached a point near Seguin, west of the Guadalupe River. There we camped for a short time to let our horses graze until dark, when we heard Captain Caldwell voice ring out: "Saddle up, Saddle up." We were soon on our way to a point on the Salado River about six miles east San Antonio, and made distance of some thirty-five miles during the night. When daylight came we shot and killed four fat beeves as we were camped there on the clear, running Salado, Captain Caldwell sent Captain Jack Hays with twenty-five man to see whether the Mexicans had left San Antonio. He had been gone a couple of hours when about five hundred Mexicans mounted on good horses forced him to take his company and retreat back to our camp. The Mexicans then took their position five or six hundred yards east of us. In a short time the entire command, estimated to be fourteen hundred men, came out with two pieces of artillery. It was about ten o’clock in the morning when they formed and began to fire on us. This was, I think, in the month of October, 1842 [September 1842], or six years after Texas became a Republic. The Mexicans kept continuous fire over us the rest of the day and could throw their small canister balls into our lines. On account of the distance we did not pay a great deal of attention to them, and kept on roasting and eating our beef, without any bread. I had a messmate by the name of Sol Simmons, and after roasting four large portions of rib we devoured the whole of them. Sol then picked up his gun and said: "I’ll go up the hill and see if I can get a shot at some Mexicans." I told him to be on the lookout, but he went on up the hill. He did not got very far, however, before being struck by a ball that hit him in the breast, breaking some of his ribs. The doctor examined his wound and said it was fatal, but his prediction was not true, as Sol got well.

[Other storytellers and veterans of the battle, Miles S. Bennet, Robert Hall , James Nichols and Andrew Sowell (to his nephew) related more elaborate, but similar, stories, see Battle of Salado--WLM].

In getting ready for the battle on the Salado, Captain Caldwell prepared us by saying that the test had come. He rolled up his sleeves and stopped in front of the men with a red handkerchief tied around his head, and made us a speech something like this:

"Boys, I have longed to see the day when I would have a chance to fight these rascals, ever since I spent some time in a Mexican prison, Now boys, the time has come, and I do not want you to shoot until you can see the whites of their eyes. If every one of you will pick your men and make a sure shot, we will whip h--- out of them before they know it."

And sure enough we did. The main fighting with the Mexicans in that battle came later in the evening, and we were in hopes of receiving reinforcements that were reported on the way. Meantime, the Mexicans charged on the right and left wings, leaving enough room in the center to play their cannon. We whipped them in about fifteen minutes shooting some of them down within twenty steps of our lines. Two hundred and two men were all we had in this engagement, but we killed several hundred Mexicans and stopped their advance.

The Dawson Massacre. Captain Dawson with a small company from LaGrange was advancing towards San Antonio in an effort to join Caldwell's forces, and came upon one section of the Mexican army just after it had made the unsuccessful attack on us. Captain Dawson had fifty-two men in his company and thirty-five of them were killed, some after they had raised the while flag; fifteen were taken prisoners, and only two of them escaped. The two who made their escape were Olsey Miller and Gonsolvo Woods. Miller was on a very fast horse and succeeded in running right through the Mexican lines. Woods, who had lost his father and brother in the battle, started to make his escape on foot, but was overtaken by a Mexican on horseback who struck him with a spear in the shoulder, Woods reached up and pulled the spear from his shoulder and instantly killed the Mexican with it. Woods then got on the Mexican's horse and made his escape. I knew both of the men who escaped very well, and also others who were in Dawson's unfortunate company. This massacre took place within about a mile and a quarter of our battleground at the Salado, but we were unable to render Dawson’s company any assistance until it was too late.

We had in our organization some very brave and daring men, including two Methodist preachers named Carroll and Devilbiss and a Baptist minister named Z. N. Morrell. "Dingle" Smith and his son were in the thickest of the fight and captured one of the Mexican soldiers and carried him to our lines [This likely refers to Ezekial Smith and son French Smith]. The Mexican reported about four hundred and eighty of their men had been killed and wounded that day and we counted forty-eight dead Mexicans left on the field after they had carried off a great number of casualties with them. We lost one man killed whose name was Jett, and ten of our men were wounded. Jett was cut off from his company by Córdova’s Indians before the Mexicans made their main attack. The Indians killed and scalped Jett as he was making a desperate attempt to save his horse. Córdova, a famous Mexican outlaw, was killed in the fight. Back in 1838 "Old Paint" Caldwell, the McCullough brothers and I, as well as others who were present in this battle, had followed the Mexican outlaw when he left Nacogdoches for Mexico with his Negroes, Mexicans and Indians, but at that time we were unable to overtake him.

Pursuit of Woll's Army to the border. After we had given the Mexicans this whipping at the Salado, we followed them over across the Medina River to a little stream called the Hondo. There Jack Hays with his picked men charged the rear-guard of the enemy and took one cannon, but could not hold it as he had only twenty-five men. In this engagement Arch Gibson and Luckey was wounded, and Bill Morrison was thrown from his horse into the chaparral but in some mysterious manner Morrison was soon back with his company. There he found his horse and was soon in the saddle again. About sunset we camped on the Hondo for the night expecting to have further plans announced in the morning. By this time we had about five hundred men in our camp, and were in hearing distance of the enemy's drums. Mayfield and Captain Caldwell made speeches that morning, but Caldwell told us he was not in favor of following this Mexican army any further. He stated his desire had been accomplished at the Salado, he said he knew we could whip them, but we could not do it without losing a good many of our men, and added: "I would not give ten of my men for the entire Mexican army." Mayfield attempted to make a speech in opposition to Caldwell, then they both stepped out in front and called for volunteers to decide the question. Captain Caldwell got at least two-thirds or three-fourths of the men, so we decided to return to our home. This was the last raid the Mexicans ever made on Texas. General Woll was in charge of these forces that invaded Texas at that time, and I think we made the "wool" fly off his command. Caldwell said the Mexican army never would invade Texas again, and they never did.

Uncle Nate's version of the Woll occupation of Bexar, the Battle of Salado and retreat to the border is similar to the Texan version related by many eyewitness participants in the action. The official Mexican description by Gen. Adrian Woll to his superiors from Mexican army archives is quite different. In the Mexican version the action is claimed a victory for Mexico and Gen. Woll was actually decorated for heroism and leadership for the expedition. Gen. Woll's reports cite "....120 who died at the hands of our Cavalry, and the 15 prisoners we took, more than 60 of his corpses remained stretched out dead in the forest; the number of his wounded must be immense, but since these were taken along on the retreat, we could only recover five of them. On our part, we had 29 dead and 58 wounded." This obviously in large part refers to the results of the Dawson Massacre. Gen. Woll further describes the encounter on the Medina River at Arroyo Hondo as a rout of the Texans " the said crowd of Texans, terrified, split up in small fractions, and retreated fleeing in all directions toward their homes."

Mrs. Dickerson and the Alamo. Now let us return to San Antonio and take up some of the events which took place there. I will say that knew Mrs. Dickerson well, as did all the Gonzales settlers. She and her baby and a Negro man were the only survivors of the battle of the Alamo. After Travis and his forces fell at the Alamo, the survivors walked to Gonzales a distance of about eighty miles. I never saw, nor did I ever hear of, a Texas soldier by the name of Rose, until just recently when I noticed an account of his death in the papers, saying he escaped from the Alamo. I do not believe there is any foundation for the report that this man was in the conflict at the Alamo in 1836, and that he escaped the fate of those martyred men who bravely fought until the last.

Texas Preachers. I was a very close friend of T. J. Pilgrim, and believe he organized the first Sunday School in Texas; at least he was first in the Gonzales settlement. A man by the name of Edwards taught the first school at Gonzales, which was in the year 1832 [This is likely David B. Edward, author of The History of Texas written in 1836, who was critical of early Texas culture in respect to morality and culture-WLM]. The first man I ever heard preach in Texas was a man by the name of Bacon. He preached at the Gonzales settlement, but I do not recall his denomination. Z. N. Morrell was a Missionary Baptist and was among the first to preach in Gonzales; this was in the early days when plenty of moccasin tracks could be found on the streets of the town every morning.

Captain Dick Chisholm was a personal acquaintance and friend of mine and often related his experiences. He was captured by the Indians in the year 1840 or 1841 near the head of Little Brushy Creek in what is now DeWitt County, not more than ten miles from where I then lived. I think he was the loneliest white man I ever saw and believe the Indians must have been of the same opinion. They pulled his eyelids open wide and after examining his eyes closely said he was "No Big Captain," and told him to go. The reason they turned him loose was that they were on their way to Victoria to steal a bunch of horses, and they knew his partner Fulcher who had gotten away on a fast horse, would report it at once. Thus a force of men would be after them, and they would not get their horses. He is the only white man I ever knew the Indians to turn loose and many of Chisholm's old friends used to say that it was his "good look" that kept the Indians from killing him.

Surveying the Gonzales-Austin Road. Captain Caldwell surveyed the road from Gonzales to Austin. Ben and Henry McCullough as well as I were in the surveying crew. About ten miles out from Gonzales our party killed a large buffalo. We took such parts of the animal as suited our choice and went on a few miles farther, where we found water. There we struck camp for the night, and after preparing some sharp sticks we soon had our buffalo on to roast. We had plenty of salt, pepper and coffee, but only a few of us had any bread. As we were surveying on up the line, we found a rich bee-tree within ten miles of Austin. After we had robbed the bees and secured plenty of honey, we felt that we were living high. Captain Caldwell was very careful to have a guard placed on duty every night, as his experience had taught him to be on the alert for Indians. Our party consisted of about fifteen men, and after completing the survey to Austin, we decided to make a visit to a Mr. Barton who lived about three miles west of Austin across the Colorado River. He had three pet bears and four pet buffalo calves. We stayed at Bartons four days and then returned to our home at Gonzales.

Indian Vandalism and Depredation. While we were away on the surveying trip to Austin the Indians came to the Gonzales settlement and killed a man by the name of Dr. Witter a few miles above the townsite. After stealing a bunch of horses, the Indians left for the hill country. There were not enough horses left for any number of men to follow them, so we were unable to pursue the fleeing Indians. These Indians would do almost anything in order to steal horses from the settlers, and the Gonzales people had many sad experiences with them. There was a man by the name of Patrick in the settlement who said he would show the Indians that his horse could eat grass, but that they would not steal him either. He locked some iron hobbles on his horse and then turned him out to graze at night. The first time the Indians found this horse they killed him, and after cutting off his feet they carried the iron hobbles with them. Zeke Williams, who lived near the Gonzales town-site, put up a stable built of logs. He chinked the cracks tight and made a strong door-shutter, locking his horse inside for protection. The Indians came during the night and pulled the chinks from the cracks of this stable and after shooting the poor horse full of arrows, they left him for dead. This was in 1831 as well as I remember. We had been living there a year or two at the time, and there were only seven or eight families living near us then. There was only one well to supply us with drinking water during the early days of the settlement, and this well was equipped with an old fashioned windlass and crank. Some of the Indians must have become curious and decided they would draw some water from the well with the windlass. It seems that the Indians must have let the crank loose after having the filled bucket partly raised, and the weight of the water caused the crank handle to hit one of the Indians on the head. The print of his full length was left on the sand the next morning with some blood stains close by.

Uncle Abe Zumwalt, who married my father’s sister and came to Texas with us, stayed all night in 1830 with a Mr. Larrison on Peach Creek above Gonzales. He had his horse tied within a few feet of the cabin door in which they were sleeping. During the night his horse began to snort and cut up generally. It was a very dark and misty night, and anyone could hardly see a horse at any distance. Uncle went outside to see about his horse, and when he put his hand on the animal’s neck, an Indian put his hand on Uncle Abe’s hand. Uncle was unable to say which was more scared, he or the Indian. He then untied his horse, pulled his horse’s head inside the cabin door, and sat up and held on to the horse until daylight. After this happening, it was reported that Uncle Abe sold his league and labor of land $600 as he decided he had rather live where it was more thickly settled.

Encounters with Comanches near Big Hill. [It is unclear exactly which Indian depredation Uncle Nate is relating here. His home near old Moulton on the Burket league was near Big Hill, the favorite path of Comanches and other nomadic tribes roving back and forth to the coast. William Ponton was killed while cutting poles in 1834, Archibald Smothers and Mr. Nunnelley were killed in 1838 while making boards near Hallettsville while the Foley/Ponton incident in which Foley was killed occurred in fall 1840 on Ponton's Creek on the Gonzales-Columbus road while they were in transit-WLM.]

In 1838 I was in the section which is now the northeast portion of Lavaca County with a party of surveyors As I left them to go to my home some fifteen miles distant, I started out to make the journey on foot. On the way I killed a year-old doe and skinned it, and then cut off the hams to take them home with me. I was then eight miles from my home and it was about eleven o’clock in the morning on a warm July day. As I was hot and tired I went down to a deep ravine and took a good, sound nap for an hour or more. Upon resuming my journey home, I came upon a fresh trail made by horses within a hundred yards of where I had stopped for the nap. After following this trail for a short distance I came to a leaning tree that a horse could walk under, but the trail went around it. I was satisfied then that it was a bunch of Indians, and they had passed right by me while I was asleep. It was frightening to know that I had had such a close call, and I began to make tracks for home in double quick time, reaching there in safety with my two venison hams.

A short time after I had reached home, there came up to the house a "Dutchman" on a horse that he had nearly run down. He said: "They nearly cotched me." His horse was named Davy Crockett and really saved the man's life by being a fleet animal. The Indians started him between the Big Hill and Andrew Ponton's place on the Gonzales-Columbus road, seven miles from where I lived and about two miles from where they passed by me in the ravine. Seven of the mounted red men chased him within sight of the house. He was the most scared of all the men I have ever seen. In his excitement he said: "How dot pig heel (big hill) did run down wit my Davy." Ponton was killed a short time before that near his home while making boards, and there were four other man killed by Indians near the foot of Big Hill. The "Dutchman" stated there were about fifty Indians in the main party.

The Hibbins-Creath Massacre. [This passage refers to the infamous Hibbins-Creath massacre in 1836 on the old La Bahia Road which was later renamed the Labordee Road-WLM].

Twelve miles from where I now live, along where Labordee Road crosses Rocky Creek, a man by the name of Hibson with his wife and two children, stopped one day to have their noon meal and to rest themselves and their team. A party of Indians rode up, and upon alighting from their horses they appeared to be friendly. Hibson divided the dinner with them; after which they passed around cigarettes, and he took a smoke with them. One of the Indians then took the man's gun and shot him dead, after which they took the wife and two children and started north. While on their way, the smallest child, which was a sucking baby, began to fret and cry. One of the Indians grabbed it from the woman and beat its brains out against a tree. This was later related by the woman who had three husbands killed by Indians. After traveling with these Indians for three or four days, she made her escape during the night. She was by this time in Bastrop County and quite a distance from home. The lady understood Spanish quite well. During a conversation one of the Indians pointed in a certain direction and said it was only three miles to a house. She thought this might be a possible chance to escape, so she made the effort and succeeded in getting away. After going some distance she found a trail which led to the house, where she retorted her circumstances and the fate of her family. In a short time word was passed along to Captain Tomlinson and his company who soon mounted their horses and were in pursuit. It did not take the captain long to find the Indian trail, and late that evening he and his men overtook them as they were making camp on a creek. They opened fired on the Indians, killed several of them, and put the others to run, rescuing the Hibson boy and returning home with him. This boy was only four or five years old at the time, but he grew up to be a fine young fellow and married one of our neighbors girls. He died in our neighborhood at a rather early age, and I helped bury him.

The Lockhart-Putman Kidnappings. This Indian depredation was committed in the year 1841, and it was in October of the same year the Indians made a raid on the Guadalupe River settlement, which was located across the river from where Cuero is now located. At that time they captured two of Andrew Lockhart’s and two of Mitchell Putman’s children. I know both families well and assisted in pursuing the Indians. Word was sent up the river as far as Gonzales and also to Ben and Henry McCullough and to Captain Caldwell, and others including me. We soon got several men together, and after we struck the Indian trail we followed it to a point near Cibolo Creek, where it pointed north. We followed this trail for three days; on the fourth day an old fashioned "blue norther" hit us right in the face. It was sleeting in a short time, and the ground was soon covered with sleet and ice. We continued to follow the Indian trail until it was completely covered from our view. It was then nearly night and I had only some summer clothes, so I came close to freezing that night. Immediately after we stopped I was detailed to go on guard, but a friend kindly loaned me a gray saddle blanket which I used around me in Indian fashion. In a short time the blanket was frozen as stiff as a board, but it offered me some protection. It continued to sleet all night, and as we could do nothing about following the trail the next morning. We decided to return home. In one of the Indian fights some time later we finally got three of these children back--two of Putman’s and one of the Lockhart's. We could never hear of the other Lockhart child. I saw the Putman girl a few years ago and had quite a long talk with her. She said it was a good thing that we did not overtake the Indians when they were heading north from the Cibolo, for they were at least five hundred strong when the sleet struck them that cold day. At the time of this writing this girl is living near Wrightsboro in Gonzales County.

[Details of this attack and kidnapping which occurred on 9 Dec 1838 while the Putnam and Lockhart neighbors were gathering pecans on the Guadalupe River south of Gonzales vary dependent on source. See Putnam--WLM]

Old Settlers, Panthers, Wolves and Other Game. Some interesting stories are told about early settlers in the first colonies of Texas, and the conditions that existed at that time. A group of men from Tennessee traveling through this section on horseback, camped near an old settler's cabin. Some of the boys came out from the cabin and gave each of the campers a biscuit, as if treating them to something now. These were hardtack biscuits, and were described as being about as hard as a terrapin. This was when flour was twenty dollars a barrel, and extremely hard to got at any price. These men got into a conversation with the settler and inquired about the price of land in that section. He told them he had seen the day when he could have bought a league of land for a pair of boots. They asked him why he did not make the trade, and he said: "H---, I did not have the boots, and I do not suppose there was an extra pair of boots in the settlement at the time."

An elderly gentleman by the name of King lived on the Guadalupe River ten or twelve miles above Gonzales. He was a clever and agreeable old fellow and had three or four good looking daughters. A party of men rode up to his gate one evening and inquired if they might stay all night with him. The old gentleman replied:

"Certainly gentlemen; light and come in. We have plenty of food, and the water and grass for your horses are fine. We have just butchered a nice, fat beef, and it is all free. My girls got so particular though, that l had to run a partition through my house and put some tom-fool windows to suit the times; I do not know what, new notions we will have to put up with next."

In the year 1841 I was living on the Guadalupe River fifteen miles below Gonzales, near where the Gonzales-DeWitt county-line is now located. As we had to get our meat out of the woods in those days, I did a lot of hunting, and remember a particular incident in October of that year while on a deer hunt. I started out in the afternoon, and it was late in the evening before I had a chance at a deer. I ran into several of them near a big thicket, and crawling to within shooting distance I shot one of them. It ran off into the high grass, which at that time was high enough to hide a deer from view. I reloaded my gun and started on the trail, as I had found plenty of blood where the deer had first fallen. All at once I heard a panther or mountain lion howling from the nearby thicket. I tried then to see if I could locate what was at hand, but I could not see because of the high grass and thick brush. So I then went on and located my deer, strung it up on a high point, then got my horse, and went three miles for my hunting dogs. The sun was down when I returned, and it began to get dark fast. In a short time the animals began to howl again so I got on my horse and went after them. The dogs were soon baying up two different trees. In the first I saw a full grown panther on a large limb walking towards the body of the tree. I fired at him, but in the excitement hit the limb instead of the big cat. As quick as thought another panther began to yell about ten steps back of me, and it continued to yell as if it were going into fits. I called to my dogs to take away the panther the ground a few yards back of me. Then calling to my oldest dog to watch the first tree, I went over to see about the young dogs and found they had three panthers in the nearby trees. After building a fire under the trees I was able to see to better advantage and managed to kill the two largest panthers--the old man and the old lady--but in the meantime the two young ones made their escape.

I have killed as many as twenty-seven wolves in one year, and most of these were the large kind that are more commonly known as lobos. I have also killed quite a number of bear and buffalo. In the early days it was no trouble to kill several deer in one day, and wild turkeys were so plentiful in some sections that hunters often killed them by the dozen. When it came to fishing, I have caught many catfish that weighed as much as forty or even fifty pounds. Sometimes it seems to me that we lived better and had better health in those early days than we have now. Most of the men wore buckskin suits and moccasins and the women and children wore homespun clothes. Practically every one lived in log cabins with adobe or packed earth floors, and slept in home-made beds which were built into the corner of the rooms and fastened to two walls. Most cabins were constructed with fireplaces which were used for all the cooking, in addition to heating, molding bullets, etc. Those who had no fireplace had to do their cooking outdoors in regular campfire style.

(Left, unfinished, in month of April 1895 by Nathan Boone Burkett, then in his seventy fifth year)

The following letter, provided by N.B. Burkett's second greatgrandson Keith Woodley of Comanche, Texas, was found in the personal effects of Kate Peavey Woodley, wife of James Edwin Woodley, the son of Martha Burkett and Thomas Jefferson Woodley. Martha Burkett was the oldest daughter of Nathan Boone Burkett. Nathan B. Burkett named a son after Capt. Scott mentioned in the letter. Samuel Scott Burkett was the first born after he returned home from the war and was a police officer in Yoakum, TX for many years.

Los Indos Jan. the 1st 1865. Dear Wife. I with pleasure take my penn in hand this New Years mroning to drop you a few lines, which will bring sum satisfaction to you I hav no doubt . I hav not receivd any letters from you since the 12 of Oct, at that time you had about 300 bushels of corn geather, I heard from you by Jacob Chesney since that time, but nothing deffinet in reltion to your family concerns, I know not how to write to you from the fact I have not receivd eny letters from home for nearly 2 months, the 11 of this month will be 5 since I left home, I hav all most forgotten how you all look, I stil hoap to see you all soon. Capt. S. L. Scott is going to town to morrow to get the clothing thar has been so much talk about, the chat is that we will start next weak but I cant say that we will for that has been the case ever since we hav been atthis place & stil we remain hear yet it is not recorded when we will leav this God forsaken country, it was never intended for white men to live in at first, it is well situated for thievs & Robbers & it is full of them. Since I last wrote you which was the 22 of Dec we found a man killed about 300 yards from our camp he had been shot in the back of the head with a six shooter, he was torn to peaces by the wolves from the appearance of the frame he had been kill about six weaks, it could not be asertaind who he was, we burried his bones, I was out hunting a few days since & found another mans Scull Boan I could find no other boans his head is thear sticking up on a bush he has been killed from the apearence 2 or 3 years, God only knows how many has been killed in this country in the same way.

Dear children, I feal it my duty to address a few lines to you, I do not know how you hav conducted your selvs in the absence of your father but I do believe that you will act honerably & just as I hav all ways taut you to do; thare is 3 great principles that I want you to observe honesty, truth & charity & be shure that you attend to your one busness & interfear with no other pursons & you will be shure to hav friends whare ever you go. I want you to be shure to Read your New Testament with grate car & obsuven its teaching is the best instructions that I can giv you, I comend you to the Lord Jesus Christ & in his car I comit you, hoping that you will be led by his Spirit & do his will in all thing purtaining to your Salvation & Redemption. Finely my dear Wife & Children, I leave you in the hands of God Almighty hoping that you will be submisive to his will in all things ma the love & mercy of our Lord Jesus Christ be with you all ways Even to the End of the world. N. B. Burkett

SONS OF DEWITT COLONY TEXAS

© 1997-2008, Wallace L. McKeehan, All Rights Reserved.