| A reader's Alamo Forum

question prompts historian Dr. Stephen L. Hardin to reexamine the story

surrounding James Butler Bonham's time in and out of the Alamo during

the siege.

I read with interest your belief that Bonham was in the Alamo only three days. I assume you are basing that on Tom Lindley's 1988 Alamo Journal article on Bonham. The theory that Bonham did not return to the Alamo after his mid-February visit to Fannin must assume that the account of Dr. John Sutherland is bogus for he has Bonham returning to the Alamo on the 23rd. I know Lindley and others have serious questions about the validity of the Sutherland account. My question is--what additional evidence are you aware of that Bonham never returned to the Alamo after meeting with Fannin until March 3rd? Gil Gillam

|

Still, there was a person inside the Alamo during the entire siege who was in a position to report on Bonham's travels. His name was William Barret Travis. In his letter to the Convention dated March 3, 1836, he explains:

"Col. Fannin is said to be on the march to this place with reinforcements, but I fear it is not true, as I have repeatedly sent to him for aid without receiving any. Colonel Bonham, my special messenger, arrived at La Bahía fourteen days ago, with a request for aid, and on the arrival of the enemy in Bexar, ten days ago, I sent an express to Colonel F., which arrived at Goliad on the next day, urging him to send us reinforcements; none have yet arrived."Earlier in the same letter, Travis asserted:

"Colonel J. B. Bonham (a courier from Gonzales) got in this morning at eleven o'clock without molestation."In a letter to Jesse Grimes, also written on March 3, he confirms Bonham's arrival date but adds a few details:

"Colonel Bonham got in today by coming between the powder house and the enemy's upper encampment."Many have supposed that Bonham also carried the February 23 "express to Colonel F." but read the passage carefully. Travis refers to Bonham as his "special messenger" and states that he "arrived at La Bahía fourteen days ago." Recall, now, that 1836 was a leap year, so figure 29 days in February. On March 3, therefore, "fourteen days ago" would have been February 19th or before the siege began on February 23. So Bonham left Béxar on February 16, arrived in Goliad on February 19, and had not returned by the time the siege began on February 23. Indeed, according to Travis, Bonham did not return until March 3. Since he mentioned Bonham by name just a few lines before would he have failed to name him again when he reported "sending an express" to Goliad on February 23? Note also that Travis made no mention of Bonham's second trip to Goliad. Since he is lambasting Fannin for his lethargy would he have neglected to report that he had twice dispatched Bonham to hurry the Goliad commander along? Unlikely.

"Yeah, but couldn't he have come back and left again before March 3." No doubt, Bonham enthusiasts will insist that must have been the case. Yet Travis, who was in a position to know, stated in no uncertain terms when he sent Bonham out and when he returned. If we can believe Travis (and why would he lie about it?) Bonham was inside the fort as a defender for three of the thirteen days.

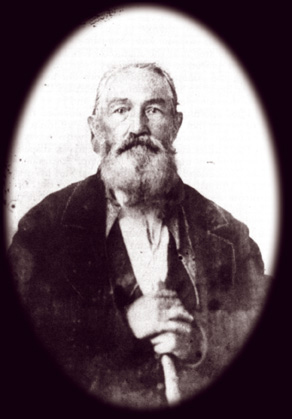

John Sutherland |

But there is another version. Dr. Sutherland says he saw Bonham riding back to the fort just as he was leaving on February 23. (See

James T. De Shields, ed., "John Sutherland's Account of the Fall of the

Alamo," Dallas News, February 12, 1911.) If true, Bonham was inside

the fort from the first day of the siege until he left on his second trip.

Lord, Tinkle, and most other traditional accounts have Bonham leaving again

on February 27. But how did they know?

As with other problems concerning the Alamo saga, one can trace this one all to Amelia William's. In a content footnote attached to the published version of her dissertation that appeared in The Southwestern Historical Quarterly, she stated the following: "Dr. Sutherland says that this courier who was sent to Goliad on February 23, was not James Butler Bonham, as many accounts state, but a young man by the name of Johnson. Bonham, so Sutherland says, returned to Bexar on February 23, after the siege had begun. He was sent out again, later, about the 26 or 27, it seems, although the date cannot be ascertained with absolute certainty." |

[For the above see, Amelia Williams, "A Critical Study of the Siege of the Alamo and the Personnel of its Defenders," The Southwestern Historical Quarterly (July 1933), XXXVII: fn. 52, p. 20.] The footnote cited is replete with qualifiers: "about," "it seems","the date cannot be ascertained with absolute certainty." Even so, when she offered her chronology of the siege (which she claims to have "compiled from all available sources"), no such qualification occurs.

"...Fifth Day, February 27. Bonham left for Goliad and Gonzales to hurry up reinforcements."Conspicuously, Miss Williams did not cite a source for Bonham leaving on that exact date for as she admitted in her earlier footnote no such source exists. The assertion that Bonham left the Alamo on February 27 was then, and remains now, mere conjecture on the part of Amelia Williams. Lord and the others appear to have read Williams's text without examining her footnotes. Once the February 27 date entered the public record and the public consciousness, it became as Holy writ.

But let's not be overly pedantic. More important than the exact date of Bonham's putative second trip is the question of the trip itself. We know that he came back on March 3. If Sutherland was correct and Bonham returned on February 23, he must have left again between then and March 3. If true, Williams's supposition that he left on February 26 or 27 would be reasonable. It would require that much time to ride to Goliad and Gonzales. At the end of the day, it all comes down to the source one chooses to accept. Travis penned his March 3 letter while on the ground, during the siege. Historians are not sure when Sutherland wrote his account or the extent to which the editor James T. DeShields may have embellished it (he was known to do that on occasion), but it was years after the fact. Still, he might have been right. If one wishes to believe that Bonham made a second ride from February 27 until March 3, go ahead. You have my permission. I have my doubts, but let's face it; there is much about those thirteen days that we just don't know and never will.

As Travis's "special messenger," Bonham rode far afield to explain the garrison's plight to as many people he could find. After the war, Bonham's brother came to Texas seeking information regarding James. Sam Houston told him that he had met with Bonham during the siege, so he may have traveled as far north as the Town of Washington. He returned to Béxar via Gonzales, so he well could have been coming back from Washington.

Recall also the dispatch Bonham carried in from Gonzales. According to traditional accounts: "He reported to Travis the failure of his mission to Fannin and the apparent end of all hope that further assistance would arrive in time." Not true. Historians now know that he carried a letter from Robert McAlpin Williamson to Travis. In this letter, which was later taken off Travis's body and published in a Mexican newspaper, Williamson informed Travis that a relief column was mustering in Gonzales. Williamson further urged Travis and the garrison to hold on since reinforcements would arrive soon. Far from riding to certain death, Bonham rode back to the Alamo to report help was on the way. So, far from "throwing his life away" to report the result of his mission, Bonham rode into the Alamo on March 3 believing that a relief column was close behind him. He appears to have remained inside the fort until its fall three days later.

Bonham's heroic status is not contingent upon the time he spent behind the Alamo walls. He probably accomplished more astride his saddle than he would have sitting on his duff inside the compound dodging Mexican shot and shell. The salient points are these. He performed his duties as Travis's "special messenger" with commitment and dogged perseverance; no man could have done more. He manned a cannon during the final assault and made the ultimate sacrifice. That ought to be enough in anyone's book. S.L.H.

![]()

Related Articles: The Fall of the Alamo: The Account of Dr. John Sutherland

![]()