SONS OF

DEWITT COLONY TEXAS French Exiles in Texas 1818 Colonists Hartmann & Millard | From the Lamar Papers Search Handbook of Texas for specific biographies

TEXAS Comprising all that has happened from the formation to the dissolution of that Colony, with the causes, and a list of all the French Colonists, together with useful information for their families and a map of the camp. DEDICATED TO

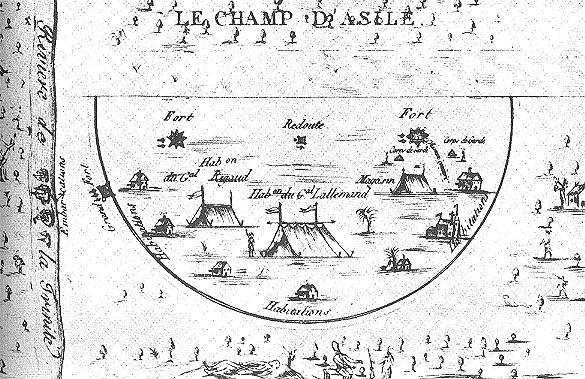

TO THE GENTLEMEN WHO SUBSCRIBED TO THE ENTERPRISE IN FAVOR OF THE REFUGEES Gentlemen. To dedicate to you an exact account of what transpired in our undertaking, which you desired to see prosper, is to perform a sacred duty. We, more fortunate than many of our comrades, have seen again that dear fatherland which we so regretfully left, of which we held such sweet remembrances. Thus it is our privilege to convey to you the sentiments expressed on the banks of the Trinity by Frenchmen always worthy of the name, when they learned that their brothers on the Seine desired not only to lighten the sorrow of absence, but to share with them in the land of their exile such happiness as they could enjoy far from the generous hands to which they were beholden for this good fortune. Proud of having aroused the lively interest of the most distinguished citizens of the greatest nation of the universe, the Texas Colonists hoped to show themselves worthy of it by determined efforts to attain prosperity which would justify the good wishes and help of their compatriots. With what pride could they, these sons of France ---so far from her---see the products of Champ d'Asile borne to the feet of their mother, as the first fruits of its gifts, as a tribute of their unwavering love for her. Alas! Your noble designs were not fulfilled, and our sweet dreams have been dispelled. Deprived of the aid which you intended for us we saw d'Asile destroyed---the refuge which you to imagine would see the peaceful end of our days which has been but too long and stormy. Envy, having fallen asleep in the world, reawakened in the new to punish us for the glory of our county to which, we dare say, some of us had contributed. Scattered over several parts of the Americas, the greater number of our companions have no hope but in your generosity; it is by means of funds collected in this munificent spirit---to assure us a new country---the they can return to their homes. More unfortunate than they when your generosity attempted to better their lot, they would not hesitate to leave behind them the horror of their present and in the march of human events, your kindness will by their gratitude. Believing, Gentlemen, that you are always anxious to Frenchmen, so often victims of circumstances which they could neither foresee nor avoid, we make so bold, then, as to publish, under your good auspices, a work destined to make known their past misfortunes, and to arouse again in their behalf the sympathy of which they are more than ever in need, we have the honor to be with respect, Gentlemen, Your very humble and very obedient servants The events which preceded and followed the 20th of March, 1815, engendered in France a sort of fermentation, which embittered every spirit. Everywhere hopes had been dashed to earth. Those who had seen them come to life no longer troubled to hide their hatred. Words of proscription, of vengeance were heard; and, although the government's head did not speak out in terms which certain individuals might have desired, the order of the 24th of July, in forcing a number of Frenchmen to expatriate themselves, aroused in others the desire to go to another hemisphere. America was the place which the greater number chose, and soon Champ d'Asile appeared as a refuge to those who were afraid of coming under the ban of that law of the 24th of July, and to others, who, seeing themselves obliged to give up a calling which they had followed with honor for many years, thought they could not do better than to try their fortunes in another land, having as their only capital the most glorious of memories, that fortitude which knows how to face adversity, and the courage which aids in surmounting difficulties that industry may triumph Such were the causes which brought about this emigration, which wrung tears from the eyes of love and friendship, and which concentrated the gaze of a great part of the French upon this spot on new continent, where brothers, companions in arms, were going to found another fatherland. Time, which stills everything and shapes the future, it be supposed that the light of forgiveness might yet shine, that the past would be lost in forgetfulness, and that a propitious future might bring back to the bosoms of their family men who were guilty only of mistakes passion had distorted into crime. It was not thought that hatred had struck such deep roots into our souls, that, at the moment when the; enlightened representatives of a noble and generous people should ask the government to open its heart to benevolence by recalling the exiles, the terrible and fearful would never would be heard, like the voice of destiny pronouncing its unchanging decree. Is then the heart of him who pronounced it thrice brass-bound? Can it be more inexorable than Providence? I this of those who each instant invoke the Eternal, who paint religion to us as the only good which can be sought on earth while giving us the hope of a better world. Was it religion that inspired him who caused that "never" to resound those walls where our legislators discuss laws which ought to insure our happiness? NO! You altar-ministers, you who bring consolation to the man who is going down into the tomb, you who calm the remorse of the criminal about to expiate his sins through deserved punishment, you let a ray of hope shine into his heart, and "never" does not escape your lips: you are for him the forerunners of mercy, thanks to you, he is launched into eternity without fear. Are they then more guilty, that they are cast aside with such a coldly deliberate hatred ? And if the most sacred dogmas proclaim that there is no pardon for which one may not hope, why should we show ourselves more unrelenting than Him from whom everything emanates? Oh, you who are called on to pronounce upon the fate of your fellows, learn that he is cruel who is only just. We are far from thinking that the King, in whose name the word was spoken, sanctioned this term of reprobation. No! The heart of a father is a spring of the sweetest, the tenderest affection, and this thought is for us a healing balm [We were not mistaken in this. His majesty has allowed Marshall Soult, Messrs. Dirat Pommereuil, and several others, to return to France]. We do not claim the power of pre-vision; our wishes cannot be considered as derogatory to authority; one then cannot blame them. Besides, who, during the past twenty years, has nothing to reproach himself for? Who has not made a few mistakes? Must we always be divided? Let us everywhere forget that we have followed different ways; let us reunite as if we had just taken a long and painful journey, and forget in the bosom of friendship and sweet confidence the fatigues and hardships of the trial. Who can hold vain self-love and foolish pride? What sacrifice should one not make for one's country? You would give your life for her. What you are refusing her is a far lesser thing. It is time that all Frenchmen were united, that they comprised one family. Let us return to our early character, let us add color of reason to our natural gaiety, which will bring out the first without harming the second. After having been too shallow, let us not try to be too deep; and in avoiding an eccentricity let us not commit a fault and even a vice. We are going to try to sketch the picture of what happened to certain Frenchmen in a place where hope led them and fatality has pursued them. Was it to teach them that they were not born to those climes and that their country called them back? Time, we like to believe, will prove to us whether we have seen into the future. We advise our readers that our narrative bears the stamp of exact truth. We do not aspire to the rank of authors; we, the simple actors in all that has happened, shall be the true historians of it. Faults will be found in the style of this work, inaccuracies which a more facile pen would have avoided. We beg, then, the indulgence of our readers. Soldiers know their swords and the art of war better than they do the flowers of rhetoric. A work on Champ d' Asile has already appeared which contains rather extensive details about that country. What we are offering to the public is a simple recital of the events which have transpired during our sojourn in Texas, between our departure and our return passage to France. This is strictly speaking, only a journal, which will, we hope, be of interest to those who sometimes thought of us when were beyond the seas. sdct ACCOUNT OF WHAT HAPPENED IN TEXAS FROM THE TIME OF THE ESTABLISHMENT OF THE FRENCH REFUGEES IN THAT PROVINCE UNTIL THEIR DEPARTURE Chapter First. After having followed a military career as much from preference as from the force of events which obliged the French to take up arms in defense of their country; having returned to civil life with no intention of again joining the army; and being still of an age when idleness is a crime and a theft from the society to which we are responsible; I formed the project of going to the United States. In those distant climes I expected to meet success, or at least a moderate fortune. This resolution taken, I busied myself with putting it into effect. Having assembled my resources, I left my family and Strasbourg, my birthplace, in the month of May, 1817, to go to Amsterdam, which I had chosen as my port of embarkation. Arrived in that city, I stayed there until the month of July, and after having made all the necessary arrangements, on the 3rd of July I boarded the American ship, Brick-Ohio, captain, E. Carmann, which was sailing for New York. The 3rd of july we heaved anchor and put to sea at 4 o'clock in the morning with west winds blowing. At 9 o'clock we passed the Pampus, at 1 o'clock we were running between Usek and Eukeisen, and we dropped anchor there in the evening on account of the calm. On the 4th we set sail at 4 o'clock in the morning under an east wind. On that day the crew celebrated the anniversary of the Independence of the United States, and at 11 o'clock we anchored in the roadstead of the Textel. From the 5th to the 9th of July the winds from the west were very violent. We rode at anchor in order to take on the water and other provisions necessary for the voyage which we were going to undertake. On the 10th of July we were under sail at 4 o'clock in the morning, but the calm forced us to cast anchor at 11 o'clock we raised it, set sail with the east wind, and in the afternoon we lost sight of land, the wind blowing S. S. E. On the 11th of July the wind veered to the west and the weather was very foggy. We changed course in the afternoon and headed north in order to round Scotland. In the evening the weather was fine with a great number of ships in sight. On the 12th we resumed our course with the east winds. The weather was rainy. At 10 o'clock a pilot-ship from Yarmouth hailed us and at 11 another. In the evening we had fine weather. On the 13th we tacked about in front of the canal, with the wind southwest; at 7 o'clock rain. At 8 o'clock the wind moved to the northwest, blowing briskly, at 11 o'clock we could see the beacons on the coast of England. The 14th, the weather and the wind did not change and we saw again the beacon; the lead was cast, found bottom at 21 fathoms. On the 15th, wind southwest; the morning, rain; the afternoon, calm. On the 16th, at 4 o'clock in the morning, we entered the canal with an east wind; at 8 o'clock we saw the coasts of France and of England; at 10 o'clock the wind shifted to the northeast; it was blowing briskly, and we put her head on; at noon the wind lessened somewhat and several sails were hauled up. The 17th, same wind, clear weather. During the afternoon the wind shifted to the southwest and we passed Bracheead. The 18th we were in sight of the Isle of Wight, north wind. From the 19th to the 31st of July continuing contrary winds, and we tacked about in front of the Lizar Cape. First to the 2d of August, fine weather, wind northwest; in the afternoon, wind blowing briskly, a heavy sea, and we were obliged to put her head on. The 3d and the 4th, same weather; in the afternoon it cleared and we had calm. The 5th and 6th, fine weather, east wind, but calm; the afternoon two young sharks were taken, about 6 feet long. From the 7th to the 15th, still a contrary wind and bad weather, the sea very rough. Afternoon we spoke to the English brig, The Sophia, of Bristol, from Milford Haven, bound for Newfoundland, at sea twenty days, and it gave us the longitude; at five o'clock another ship in sight. From the 16th to the 19th same weather and same wind. 20th. North wind and calm. 21st. Calm. In the evening we had a slight breeze from the S.W. 22d. Wind northwest; in the evening the wind settled into the north blowing very briskly. 23rd. Wind E. S. E., calm; the evening a breeze from the W. 24th. Southwest wind, continual rain. From the 25th to the 28th, same weather, very warm; in the evening the wind shifted to the north. 29th to the 30th. Wind N.N.E. At daybreak we saw away to the W.S. W. Graciosa, one of the Azores islands, fine weather. At ten o'clock, the sight of St. George and Tercere, and a three-masted Dutch boat heading east; at noon we saw the famous mountain-peak, and at three o'clock the island of Fayal. 31st. Wind N. N. E. In sight of the above islands, and we headed for Fayal. At six o'clock we saw a three-master which steered for us. At seven o'clock her ship's boat came alongside, and we learned that it was a Dutch boat, named The America, coming from Batavia and bound for Amsterdam, having eleven days of sailing ahead of her. We bought of her two bales of rice, and we wished each other bon voyage. Towards evening, almost calm, we sailed between Picko and Fayal, west wind; at 8 o'clock we anchored in the roadstead of Fayal, in 20 fathoms of water; at midnight a great west wind rose and we were obliged to throw out our main anchor. In the evening, before anchoring, our captain went aboard a three-masted Dutchman who was in the roadstead in order to secure information about landing; he was informed of the location of the currents which would undoubtedly have cast us upon the rocks. We put our skiff into the water with the purpose of towing the ship into port. On the first of September, in the morning, we signaled to have the customs men sent on board; they arrived shortly after the declaration had been made; the captain, as well as the passengers, who numbered ten, went ashore in order to purchase enough necessaries for the remainder of the voyage. There were several English and Dutch ships in the harbor. I cannot give many details about this island for we stayed there only a day: it has considerable trade in Picko wines, which are excellent; the harbor is small, but fine and safe. The 2d of September. Wind N.N.E. fresh; at 8 o'clock the customs officers returned aboard, and shortly afterwards we heaved anchor and set sail; in the afternoon we lost sight of land; the 3d, calm; the 4th, south wind; the 5th, calm; the 6th, N.E. wind; in the morning we spoke to a Spanish schooner, coming from Porto Rico and bound for Santa Maria, having fifteen days sailing ahead of her. From the 7th to the 13th almost continuous calm. The 14th, at 9 o'clock we caught sight to the south of a ship which pursued us under full sail. At 6 o'clock he asked for our standard, launched his boat with an officer and ten men, who came aboard to examine our papers; we recognized him as the freebooter, commanded by Captain Taylor. After that, they re-embarked and set out in pursuit of a ship which was in sight to the northwest. From the 15th to the 18th almost continual bad weather; nothing new; the 19th calm, west wind. During the day we harpooned several dolphins; and in the afternoon, as our captain was hurling his harpoon over the bowsprit he fell overboard; we succeeded in saving him. In the evening there were violent squalls. From the 20th of September to the 12th of October nothing extraordinary happened; we experienced considerable bad weather; at 9 o'clock we threw out the lead which grounded in yellow sand at 35 fathoms. At 11 o'clock another sounding brought up mixed sand from 24 fathoms. The 13th of October, west wind; took several soundings and found bottom at from 12 to 15 fathoms. In the afternoon we saluted an American schooner, The Anna, from Philadelphia bound for Providence. On the 14th of October, wind N.N.W. At 6 o'clock in the morning it was with great pleasure that we saw land; tacked about during the remainder of the day before the entrance to the river; continuous sail; in the afternoon we reached the open sea. The 15th, wind N.N.W. Weather fine. In the morning we steered for the river, and at 8 o'clock in the evening the beacon; we hung out the signal-light, and shortly afterwards we had the pleasure of having a pilot on board; at eleven o'clock we anchored in the river on account of the bad weather. On the 16th we sailed; fine weather; the captain with a passenger went ashore at New York and we headed for that city. We arrived about one o'clock. New York is the first commercial city of the United States, and the best defended because of superb batteries established along the Hudson. I remained ten days in New York, and then set out for Philadelphia, where, I had been told, I would find French people, and the leaders in the project to found the Texas colony. As soon as I arrived I presented myself to the Generals who were in command of the expedition. I was welcomed like a brother, like a friend. And during the month of November and the first days of December we all worked together, gathering what was necessary for the organization and establishment of the colony. sdct Chapter Second Seventeenth December. We heaved anchor and set sail at ten o'clock in the morning, with north winds, in the American schooner Huntress, under the command of Lieutenant-General Rigaud. The same day, at two o'clock in the afternoon, we anchored in the river. 18. Set sail at 8 o'clock in the morning, and anchored at 2 o'clock in the sight of Newcastle. 19. Set sail at six o'clock in the morning, and entered the open sea at eleven o'clock in the evening. At ten o'clock an Italian servant of Colonel Jeannet fell a victim to a cowardly assassination committed by some rogues who had caused certain false suspicions to rest upon him. As soon as we reached our destination, they were expelled from the colony. On the 20th, at one o'clock in the morning, we were surprised by a great tempest and were obliged to bring her head around. North wind. On the 21st, same weather, and very cold; the whole crew had their hands and feet frozen; many of the ropes and irons of the rigging broke. On the 22nd, at 10 o'clock in the morning, the weather began to clear, and all hands set about repairing the damages. Northwest winds. The 23rd, fine weather, south wind. From the 24th to the 27th, dead calm. On the 28th there was a good breeze and we arrived in sight of the island of Abaco. On midnight of the 29th we arrived off the great Bahama Bank. On the 30th, at 10 o'clock in the morning, we had a three-masted American ship in view, which had run up its distress signal; we headed for it, and it launched its small boat. The second mate came aboard, and we learned that a tempest had cast them there, after having damaged their rudder and carried away several of their sails. For a week they had remained in this position, making the necessary repairs for the continuance of their voyage; they begged us to make mention of this in the newspapers as soon as we arrived. At 6 o'clock we anchored, for fear of going on the rocks. On the 31st, at 5 o'clock in the morning, we set sail with a west wind; in the evening, dead calm. On the 1st of January, 1818, a dead calm, and the sun rose radiant. On the 2nd, at one o'clock in the morning, we passed the Bahama Bank; north wind; the rest of the night, calm; at 5 o'clock in the morning a slight breeze came up and we saw shortly afterwards the shores of the island of Culo ; the weather was very warm; at 6 o'clock in the evening, in sight of Havana, stormy weather. On the 4th we lost sight of Havana, and at 6 o'clock we saw the Island of the Turtles. North wind. From the 5th to the 7th, nothing new, same weather, in the evening except that on the 7th we had a violent storm. From the 8th to the 13th, west wind and several squalls. On the 14th, at 10 o'clock in the morning, we saw a ship to the northwest, which we recognized, as a brig, heading for us; at 4 o'clock in the evening it ran up a Spanish flag and launched its small boat, carrying an officer and four men. When it had drawn alongside of us, we learned that it was a prize taken from the Spaniards by the freebooter Couleuvre, and that it was bound for Galveston. The captain begged us to let him have some biscuit and tobacco; in exchange he gave us Spanish wines, figs, oil, olives, etc. On the 15th, calm; at 8 o'clock the Spanish prize sent us her skiff with various refreshments; in the evening a good breeze, still sailing together. The 16th, southwind, sailing northwest. It was with great pleasure that we caught sight of Galveston at 8 o'clock in the morning. At 11 o'clock we anchored in the roadstead, in seven fathoms of water. At noon the pilot came aboard to take us into the harbor. At 3 o'clock we went aground on a bank where we were obliged to anchor and wait for the tide. General Rigaud, accompanied by Messrs. Douarches, Jeannet, Schultz, Hartmann, Groningue, got into the boat to go ashore to find Sieur Lafitte, owner of independent Mexican corsairs, acting in capacity of governor, to insure the safety of our debarkation and the establishment of our provisional camp. From the 17th to the 18th, in the roads. At noon M. Lafitte came on board; we succeeded in getting afloat, and the landing was accomplished. At 2 o'clock in the afternoon we busied ourselves in constructing a camp to shelter us from the inclemencies of the weather during our sojourn in this desert island. Galveston is an island occupied by independent Mexicans; there is not a single tree to be found [in the margin a hand-written note says there are four plum trees], in consequence, apparently, of the floods to which the island is often exposed, being almost on sea-level. Properly speaking, it is only a calling port for the vessels which want to cast anchor in the bay, to cruise about or to make repairs. We remained on this island until the beginning of March and during that time lived by fishing and hunting, in order to economize in our provisions and salt meats. The first days of March were of good augury for us. General Charles Lallemand, head of the colony, arrived with a great many other colonists. Joy reigned among us; we forgot our weariness and our misfortunes and gave a little party, such as was permitted by circumstances and our situation. Gaiety, frankness and sweet out-pourings of friendship characterized our celebration in place of the luxury, extravagance and envy which make European gatherings so fastidious. Patriotic songs resounded; we drank to the happiness of our dear fatherland, to our friends who still lived there, to our good fortune, to the success of our undertaking, and to the prosperity of the colony we were founding. On the 10th of March, in the evening, we embarked, and it was agreed that we should meet at the head of the bay. Our little fleet was composed of 24 ships; scarcely had we reached the open bay when a very violent storm arose and scattered us. The darkness of night made our situation still more critical; several of the boats leaked badly, and were for a long time on the point of being swallowed up. The greater number of the boats arrived, however, without accident at the place appointed for the meeting, and we were careful to light fires in order to rally those which were still separated from us. Unfortunately, the ship on which were our brave comrades Schultz, Larochette, Hartmann, kieffel, Monnot, Fallot, Bontoux and Gilbal was delayed longer than the others. She was leaking so badly they were obliged to throw overboard the provisions they carried, as well as their baggage; in fact, everything they had, in order to empty the water which was pouring in. The seas being very high, they expected every moment to founder; undoubtedly they would have done so if they had not had the good fortune to touch on a little shoal, where they remained until midnight. Relief came to them from Galveston, our friends there having heard the cannon shots which they (the crew) continued to fire as a signal of distress; fortunately they all were saved. Another boat on which were our unfortunate companions Majors Voerster, Genait, Ferlin, Meunier le Rhonuillet, and the major's servant, was not so fortunate. The waves sank it soon after its departure. Sieur Genait was the only one who escaped. After swimming for three hours, he succeeded in reaching the bay, where, overcome with weariness, and half dead, he found a little sand bank where he rested. It is difficult to express the grief we felt on learning of this misfortune. Sincere tears fell for our companions; each of us mourned among them a friend and brother; we were all one family. How eloquent our grief was! What a funeral oration was the praise which we accorded those whom the tempest had torn from us! All had given proof of courage, devotion, and bravery, and had a hundred times braved death on the battlefield; the sea ended their careers, just as they expected to find rest and forget the injustice of Fate in friendships and in the fairest and purest enjoyments. It is thus that Fortune laughs at our plans. She shows us a brilliant future; our eyes are fixed upon the picture; we advance, little heeding the abyss which is beneath our steps; it engulfs us, and there is life and the span of our hopes: Poor mortals! Why dream so many dreams? On the 11th in the morning, as soon as all the boats were united, we set sail in fine weather, and in the evening all pitched camp near Red-fish Bank. On the 12th and 13th, bad weather and rain did not permit us to continue our way. These two days seemed interminable to us. It was impossible to give ourselves up to hunting and fishing, the only amusements offered us; and, although there were so many of us that conversation should not have been lacking, it often languished. Some amongst us, however, had the talent of renewing it by their gaiety and witty words. It was not until the morning of the 14th that we set out. We arrived at what is known as Perrey Point where we camped until the morning of the 16th. Generals Lallemand and Rigaud then decided to go on foot to Champ d'Asile situated near the Trinity River, at about 20 leagues from the Gulf of Mexico, and they set out with a detachment of a hundred men; the remainder were left to find the river, and bring up the supplies and ammunition, under the orders of Colonel Sarrazin, who thought we were perfectly familiar with the river's mouth. We expected to arrive at our destination and rejoin our companions on the following day. Unfortunately this hope was not realized, and our luckless comrades were on the point of falling victims to the delay. They had taken provisions for only two days; on the third and the fourth, hunger made itself felt desperately, and each sought means of satisfying it. It was thought that a precious and healthful discovery had been made in a plant which looked much like lettuce. It was cooked and eaten; scarcely was this done when the dangerous results were felt---it was a violent poison. A half-hour after this fatal meal all those who had partaken of it lay stretched upon the ground, wracked by the most terrible convulsions. Generals Lallemand and Rigaud and Surgeon Mann were not stricken with this illness, for, although tormented by hunger, they had been prudent enough not to taste the venomous herbs. It is impossible to describe the frightful predicament in which they found themselves. Surrounded by ninety-seven bodies whose distorted features threatened early death, they were unable to do anything toward relief, for the supply of medicine had been left on the ships. What could they do? What was to become of them? What resolution was there to take? In the New World the antidote grows beside its poison; but how could it be found, and how were they to know it? Those are the questions Generals Lallemand and Rigaud, and Dr. Mann asked themselves. In this state of anxiety they were prey to the darkest reflections, when chance, or rather an unexpected piece of luck, led thither an Indian of the Cochatis tribe. He was a good angel sent by Providence to snatch our friends from the death threatening them. He is surprised to see them in that state; he is shown the plant which caused the misadventure; he raises his hands and his eyes toward heaven, utters a sad cry, leaves with the swiftness of lightning and returns a few moments after with some plants he has gathered. These were boiled according to his directions, and then, with the aid of a piece of wood used to open the mouths of the poison victims, each one was made to drink a potion; soon afterwards they regained consciousness, and came entirely to themselves. They still suffered, however, for several days from their imprudence; but they experienced in the end no bad results. It is easy to imagine our gratitude to the good, kind savage who appeared to attach no importance to the service he rendered us. This humane act seemed quite a natural thing to him. What an example this Indian is for civilized peoples. It is rather the instinct of nature which leads us to virtue, to kindheartedness than all the highly wrought precepts of conscious eloquence. Words escape from the mouth; but the desire, the wish to put them in practice, does not always move the heart to action. Good savage! The name of this nation shall never leave my memory. The refugees of Champ d'Asile raise an enduring monument to you in their hearts; it is based on thankfulness and friendship. We have Gallicized many words which do not produce so vivid an image as that of Cochatis; and we wish that to everyone it might become the symbol of kindness and humanity. Our readers will be glad to pardon us this digression in behalf of this motive of humanity. If the beginnings of our misfortunes have interested them, they cannot be insensible to the expressions of our gratitude. sdct Chapter Three It was not until the sixth day after their departure that the boats joined the detachment which had gone on foot to Champ d' Asile, arriving at the camp which had been established on the banks of the Trinity. They had gone too far out to sea and had not immediately found the mouth of the river. This delay, as has been seen, subjected us to the greatest misfortunes, particularly in a wild, uncivilized country, all of whose products---by the test we had made of them---seemed poisonous. On their side, our comrades were not less troubled about our fate; they knew we had supplies for two days only, and that famine would soon assail us. We had accused them, for misfortune makes people unjust and suspicious-little amenable to mature consideration. All we could do was encourage each other to resignation. Some among us, and they were in the majority, displayed great strength of character, proving that adversity could not dismay them. The silence that reigned and the morose expression of every one gave evidence of the feeling to which our spirits had fallen prey. Generals Lallemand and Rigaud, setting an example of fortitude, consoled us and kept our hopes alive; but words are necessarily feeble shifts against misfortune. Finally the arrival of the vessels restored us to plenty: An account of what we had gone through made our comrades shudder. We soon forgot our griefs upon the breast of friendship, and the past was no longer anything but a dream. As soon as provisions, supplies, and other necessities were unloaded we busied ourselves with laying out a provisional camp and providing shelter from the vagaries of the weather. Next we were organized into troops, Generals Lallemand and Rigaud naming the leaders. Once this organization was completed, the plans of four forts were outlined. The first, situated on the right of the camp, was called Fort Charles, from the name of the General-in-Chief; the second, Middle Fort; the third, Fort Henry, which was on the left and communicated by a covered roadway with two guardhouses established in the camp. The fourth, placed to the right of the stockade of the camp, on the shores of the Trinity, defended the banks and covered the three other forts. It was called the Fort of the Stockade, and had three pieces of cannon. Fort Charles had two pieces; Middle Fort one; and Fort Henry two; in all, eight pieces of cannon formed our artillery. sdct

Everyone set to work with the greatest industry. The Generals worked at our head, and General Rigaud, although in advanced years, gave way in nothing to the young men: He was to be seen with pick and spade in hand, never a moment idle, directing all of us. Working hours were set from 4 to 7 o'clock in the morning and from 4 to 7 in the afternoon. Operations were directed by Messrs. Mauvais, Guillot, Arlot and Manscheski, artillery officers. Between working hours each man might attend to the building of his own house or the cultivation of his garden. In a very short space of time these forts were reared, as if by magic, and they were of astonishing strength. The principles of military science had been strictly adhered to, and the fortifications raised by the famous Vauban, or the best officers in the spirit of our times, could offer nothing better. We all consecrated to this work a certain amount of pride; and we were, so to speak, at once pioneers and engineers. The Stockade Fort was built of great trees, and was so solid it could easily have held against any attack. The powder magazines and the colony's supplies were deposited there. The private houses were laid out on a circular plan in a wide space above the forts. They were built of big trees joined together in block-house fashion, bulletproof and with loopholes, so that each one would have to be attacked separately. In the rear center was General Lallemand's house; a little farther on, at the right, was the store-house. General Rigaud had his house above Fort Henry, near the two guard-houses. The ensemble view of the camp was very pleasing. This rustic and war-like picture had something charming about it which it is difficult to convey: before the camp a wide plain; behind it the thick evergreen trees, whose tops were lost, so to speak, in the clouds; to the right rolled the Trinity River, watering the borders of the colony, to lose itself in the Gulf of Mexico. On the far bank were forests stretching away as far as the eye could reach. The left and rear of the camp were sheltered by forests to protect us from tempests. This landscape, as can be understood, had about it something picturesque and majestic; to visualize it, one has only to glance at the map accompanying this work. As we have already said, between working hours the colonists cultivated their gardens, and the very fertile soil responded to our labor. Vegetation was rank, and the earth was soon covered with plants and fruits. Messrs. Hartmann and Fux were the first who had fruit. The melons especially were of rare beauty and extraordinary size; as were all the plants set out in the earth---it gave us back with interest everything we confided to its bosom. It seemed that it was trying to recompense us by its abundant yield for our separation from the fatherland, and repay us for our choosing it as a place of refuge. We had also made several plantings of Naquidoche, which did very well; but we did not stay long enough in the country to reap the fruits of our labors. I am persuaded that tobacco would eventually have been a very resourceful branch of industry for the colony if we had given more extensive care to its culture. SONS OF DEWITT

COLONY TEXAS |