![]()

In the Alamo's Shadow

BY RON JACKSON

For one moment in time, a young black man captivated an

audience comprised mainly of the signers of the Texas Declaration of Independence. The

man's name was Joe, an American-born slave, and one of the few survivors of the March

6,1836, Battle of the Alamo.

Joe's account of the grisly battle solved the mystery of the besieged Alamo garrison for the Texas Revolutionary leaders, many of whom had had friends and relatives within its walls. His story also spelled out the gravity of the situation for the Texas cabinet as the invading Mexican Army crossed the Texas frontier.

Over 161 years later, Joe's story has an impact of a different kind.

Slavery was the only life known to Joe, who was born into bondage somewhere in the southern region of the United States around the year 1813. He was sold in 1834 to William Barrett Travis, and it was by his side Joe was thrust into one of the most heroic chapters in Texas history.

Joe accompanied Travis to San Antonio de Bexar in February 1836 and into the Alamo, a crumbling, adobe mission then being used as a military garrison by the fledgling Texas army. Travis, a fiery lieutenant colonel, would become the commanding officer of the Alamo shortly after his arrival.

By February 23, a grave situation had developed. Some 1800 to 2500 troops under Mexican General António López de Santa Anna laid siege to the Alamo, and Joe found himself among some 200 defenders trapped inside.

In the fateful, early-morning hours of March 6, freedom probably took on a whole new meaning for Joe. Creeping silently toward the Alamo in organized columns, the Mexican troops launched their final assault under a moonlit sky. Tensions mounted until one soldier in the ranks shouted,"Viva Santa Anna!" Another cried, "Viva la Republica," and hundreds of voices rang out.

The surprise was ruined.

Texan Captain John J. Baugh, startled by the enemy's cries in the night, dashed across the Alamo compound. "Colonel Travis!" he yelled. "The Mexicans are coming!"

Travis sprang from his cot, grabbing his double-barrel shotgun and sword. He called for Joe to take his gun and follow. The two sprinted to the north wall battery through a maze of defenders scrambling to their positions.

Joe heard Travis shout as he ran: "Come on, boys, the Mexicans are upon us and we'll give them Hell!"

From the top of the north wall, Travis discharged his shotgun into a crowd of onrushing Mexican soldiers. Joe followed his master's example. Within seconds, a slug drilled Travis in the forehead, sending him sliding down an earthen embankment to his death.

Joe promptly retreated into one of the rooms within the compound. From a loophole, Joe fired his gun several more times amid the desperate hand-to-hand combat that ensued. Horrific screams of the dead and dying echoed in his ears until all he heard was sporadic gunfire. Joe huddled in a corner.

With the fighting all but over, Mexican troops began to search the vast compound, room by room, for any survivors.

"Are there any Negroes here?" a voiced called out in broken English.

Miraculously, Joe had survived the carnage. Joe stepped out from the darkness of his hiding place and replied, "Yes, here's one."

Two Mexican soldiers immediately lunged at Joe. One fired a round of buckshot into his side and the other made a thrust with his bayonet, grazing the frightened slave. A Mexican captain named Marcos Barragan beat the soldiers away in an act that undoubtedly saved Joe's life.

Joe's presence at the Alamo has been well chronicled by historians, but

nonetheless reduced to a footnote in the fabled Texas story. He is often regarded as the

lone black man in an otherwise white, western adventure. In truth, there were several

black people inside the Alamo compound at the time of the final assault. Joe even

said so himself.

| One such person, a black woman, was seen by Joe after the battle, "laying dead between two guns." | |

|

Was she simply frightened and caught in the crossfire? Or did she also take up arms as

Mexican forces poured over the Alamo's battered walls? Survivor Juana Navarro de Alsbury told Texas Revolutionary war veteran John S. Ford years later that she saw a black woman after the battle. Alsbury said the woman escorted her and her one-year-old son, Alejo, to her father Don Angel Navarro's house in La Villita and that the woman belonged to Colonel James Bowie, who laid dead in the Alamo. |

Alsbury's escort may or may not have been Bowie's female cook Betty, who was in a kitchen area within the Alamo after the battle. Betty was with a slave named Charlie, a broad-shouldered man with fear in his eyes. Charlie tried to hide after the battle, only to be pulled from his hiding place by a group of Mexican soldiers.

In a desperate rage, Charlie grabbed the diminutive Mexican officer in front of him and

used him as a shield as the soldiers lunged with their bayonets. The powerful Charlie

parried each thrust with the body of the officer until the Mexican soldiers broke down in

laughter.

| The frightened officer promised to set Charlie free if he put him down

safely. Charlie obliged and was set free as promised. Rumor was he escaped to

Mexico. Another Bowie slave named Sam has often been credited as an Alamo survivor, although the credibility of these reports remain shaky. Bowie did own a slave named Sam who accompanied him on a slave-trading trip from Galveston well before the Texas Revolution. From there, Sam fades from recorded history. Some historians have apparently made the leap in logic. The "faithful" Sam must have been by his side to the heroic end. Unfortunately, the world may never know. |

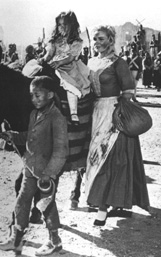

Scene from

John Wayne's The Alamo. Travis's servant Joe--described by many

19th century sources as a "slave boy" despite his adult age--in

John Wayne's movie becomes indeed a young boy, "Happy Sam,"

shown here accompanying Susanna Dickinson (Joan O'Brien) and her

daughter (Aissa Wayne) out of the Alamo after the battle. (United Artists,

1960) Scene from

John Wayne's The Alamo. Travis's servant Joe--described by many

19th century sources as a "slave boy" despite his adult age--in

John Wayne's movie becomes indeed a young boy, "Happy Sam,"

shown here accompanying Susanna Dickinson (Joan O'Brien) and her

daughter (Aissa Wayne) out of the Alamo after the battle. (United Artists,

1960) |

The identity of these black people in the Alamo are shrouded in mystery.

Slavery was illegal in the Mexican province of Tejas prior to the outbreak of the Texas Revolution. Emigrants and Tejanos skirted the law by simply calling their slaves "99-year" indentured servants or listing them as dependents. Mexican officials were also guilty of loosely enforcing the law. Thus, slaves weren't always listed on census records, wills, and other legal documents.

Bowie's estate, for instance, listed no slaves. Yet make no mistake: The legendary knife fighter, who once dealt in the slave trade with pirate Jean Lafitte, owned slaves.

One interesting account of a Bowie slave named Jim was recorded by writer Andrew Jackson Sowell in his 1900 book, Early Settlers and Indian Fighters of Southwest Texas. . .Facts Gathered From Survivors of Frontier Days. In the account Bowie orders Jim to make a dangerous dash for water during a standoff with a band of Comanches.

The story pokes fun at the frightened slave as he narrowly escapes with his scalp. But what makes the account fascinating to historians is Sowell's report that "this negro lived for many years after the death of Colonel Bowie in the Alamo, and went by the name of 'Black Jim Bowie. 'Was 'Black Jim Bowie' also in the Alamo?" As in the case of Sam, the answer may forever elude historians.

So who were these black people? And how did they end up inside the doomed Alamo garrison?

Not all of the blacks in the Alamo may have been slaves.

Abolitionists Benjamin Lundy noted the presence of at least two free blacks in Bexar on a trip there in 1833, two years prior to the start of the revolution. On August 24, 1833, Lundy penned in his diary, "There lives here in Bexar, a free black man, who speaks English. He came as a slave first from North Carolina to Georgia, and then from Georgia to Nacogdoches, in Texas....He now works as a blacksmith in this place."

Lundy also met Felipe Elua, a black Louisiana Creole slave who purchased his freedom for him and his family. Lundy wrote of Elua, "He had resided here twenty-six years, and he now owns five or six houses and lots, besides a fine piece of land near town [Bexar]....He has a sister, also residing in Bexar, who is married to a Frenchman."

Other free blacks may have arrived in Bexar by 1836, and may have found refuge in the Alamo just as some in the local Tejano population did.

Still others may have fled the area when rumors first hit Bexar of the Mexican cavalry's appearance at Leon Creek, a mere eight miles outside of town.

Five days after the Alamo's defeat, Mexican officer José Enrique de la Peña noted in his memoirs that while on the banks of the nearby Colorado River, "We met several natives, a mulatto woman, two Negro women, and several Negro men, who were very useful in making the crossing and who washed our clothes."

Black people were indeed in the area and dotted throughout the Texas frontier.

Peter, a slave owned by Wiley Martin, was definitely in the vicinity and probably entered the Alamo in December 1835. The elderly Martin wished to free Peter before his death, and in 1839, made a plea to the Texas senate by stating, "That during our struggle for Independence [Peter] rendered material aid to the government by Hauling [with his own team and at his own expense, military stores and provisions for the use of the Army during the period they were stationed before Bexar in 1835."

Peter rendered material aid to the government. |

Martin received his wish in 1842. Peter became one of only two adult slaves manumitted in the Republic of Texas and allowed to remain in the country as a free man. Peter, who had already amassed a fortune of $16,000 prior to the ruling, made the most of his freedom. He worked as a peddler and cook, and hired his wife from her master so his family could remain together. But Peter was not alone in his service.

Cary, the only other Republic of Texas slave to be manumitted, was also "of much service in carrying expresses" during the war. In addition, Captain Josiah H. Bell dispatched his slaves Peter and Sam to help guard families near the battlefront in April 1836. Whether or not any of these men aided the Alamo garrison is unknown.

Like Joe, most of the Alamo's black populace probably didn't have a choice whether or not they were present. A number of Alamo defenders owned slaves: Micajah Autry, Mial Scurlock, William R. Carey. Even courier Juan N. Seguin, who left the Alamo February 25 to rally reinforcements, and his family were known to own slaves. Any one of these men could have brought their servants with them to Bexar.

Evidence shows Carey probably did bring a slave into the Alamo. Years after the battle, Carey's father, Moses, traveled to Texas to settle his son's estate. The elder Carey received $198.65 for his son's military service. On June 25,1839, Moses filed a document stating a "private servant" may have died with his son at the Alamo.

Scurlock might have also been accompanied by a slave. In 1834, Mial and his older brother, William, moved to Texas from Mississippi to reap the rewards of the vast Mexican province. They entered Texas through Louisiana via the Gaines Ferry. With them they brought supplies and slaves, Henry Smith, John Scurlock, an eighteen-year-old woman named Easter, and her four-year-old son, Denis.

Easter and Denis (later renamed Dave Dennis) lived in a San Augustine hotel with William for a time. William, a noted hunter, paid for their room and board with the wild game he brought back from his hunts. Easter chipped in by working at the hotel.

Henry Smith and John Scurlock, meanwhile, worked side by side with Mial to build a log cabin on the younger Scurlock's 640 acres in the Sabine District. Mial and his slaves cut timber for the cabin from a nearby forest and hauled the wood on their backs. By late 1834, the bachelor Mial and his slaves moved into the new cabin.

According to family legend, Henry Smith, John Scurlock, Dave Dennis, and later Dick Dennis were all rumored to have been the o£ spring of William Scurlock. Henry and John were said to be the older half-brothers of Dave and Dick. If true, this would have made Mial an uncle.

Did Henry and John ride with Mial into the Alamo, and like Joe, survive? Or did Mial leave them home when he and William joined the fight for Texas independence?

Loyalty would not have been out of the question.

James Robinson came to Texas in March of 1836 bound by indentured servitude to Robert Eden Handy. Upon his arrival, Robinson refused a passport that would have carried him back home to his friends and family and begged permission to remain and share the fate of those who met the enemy." Robinson was allowed to join the Texas army with Handy.

A similar case might have occurred with the private listed only as "John" on early Alamo muster rolls. John is identified as a clerk in Francis L. DeSauque's store. DeSauque left the Alamo shortly before the siege began to obtain some provisions for the garrison. He was executed roughly a month later at Goliad by the Mexican army.

John, on the other hand, would become another fallen hero at the Alamo. But there is no other evidence suggesting John was black.

Another possible slave at the Alamo may have been a woman named Sarah.

In 1831, Ezekiel Hays of New Orleans filed the first of six petitions against Patrick Henry Herndon for the return of his slave, Sarah. Hays claims Herndon ran away with her and brought her to Texas.

Herndon died with the rest of the Alamo defenders on March 6, 1836. Was Sarah with Herndon at the time? Was she the dead woman, laying between two guns? Or, if she was present, did she survive?

Black people probably had as good a chance of surviving the desperate, chaotic battle as anyone else. Mexican commanders made it clear during the Texas Revolution that they were not at war with the black person, whom they viewed as a victim of the Anglo-American's brutal work system.

General Santa Anna himself made Mexico's position quite clear as he prepared to invade Texas in February 1836. He wrote to his minister of war and marine at the time: "There is a considerable number of slaves in Texas who have been introduced by their masters under cover of certain questionable contracts, but who according to our laws should be free. Shall we permit

those wretches to moan in chains any longer in a country whose kind laws protect the liberty of man without distinction of cast or color?"

Joe probably owes his life to this belief

At least one black man witnessed the fall of the Alamo from outside its walls. Ben, an African-American drifter, served as a cook for Santa Anna. From a window in town, roughly 500 yards from the Alamo, Ben watched as rockets signaled the start of the famed battle.

Under the illumination of the rockets, Ben saw scores of Mexican soldiers at the foot of the Alamo's walls. He later reported that the sound of cannon? musketry, and rifles was tremendous, and that after the battle, Colonel Juan Almonte remarked to Santa Anna, "Another such victory will ruin us."

Ben then had the unpleasant task of pointing out the bodies of Bowie and Travis, whom he claimed to have known.

Sometime in the aftermath of the battle, Ben was ordered to escort Alamo survivor Susanna Dickinson and her baby, Angelina, past the Mexican picket lines and along the beef trail to the town of Gonzales. It was there, in Gonzales, that Dickinson gave one of the first eyewitness accounts of the Alamo massacre, sparking what became popularly known as the Runaway Scrape.

Citizens of Gonzales and settlers in the surrounding areas responded to the news of the Alamo's defeat by fleeing in a mass exodus toward the safer, eastern settlements. Leading the way was the retreating Texas army under the hesitant leadership of General Sam Houston.

Somewhere in the crowd was Ben.

As fate would have it, Ben became a cook for Houston before the buckshot had stopped flying in the war.

Of all the blacks who played a role in the Texas Revolution, however, none is remembered more than Joe. The twenty-three-year-old Joe survived the butchery at the Alamo and stood face-to-face with

the infamous Santa Anna, a man he described as tall, thin and plainly dressed like "a Methodist preacher."

Joe was detained after the battle in Bexar, where he was interrogated and then forced to watch a grand review of Santa Anna's battle-hardened Mexican army. With his force of over 1,800, Santa Anna boasted to Joe he could march all the way to Washington, DC, if he wanted.

Obviously, Joe wasn't too worried.

After accompanying Ben, Dickinson, and her baby to Gonzales, Joe ended up before the Texas cabinet at Groce's Retreat, where he calmly spoke of the Alamo's fall and of Santa Anna's threat.

For all his efforts, Joe was returned to the Travis estate near Columbia, where he remained until making his escape in 1837, Joe and an unknown Mexican man disappeared one day with two fully equipped horses. A notice for Joe's return was published by the executor of the Travis estate in the Telegraph and Texas Register on May 26,1837.

A $40 reward was offered for his return. In the notice, Joe was described as "about twenty-five years of age, five feet 10 or 11 inches high, very black and good countenance." The notice ran three months and was discontinued August 26, 1837.

One legend tells of Joe returning to Alabama after his escape to tell the Travis family of his master's death at the Alamo. He is also said to be buried in an unmarked grave in Brewton, Alabama.

Joe was last reported in Austin in 1875 before fading from history.

No one really knows for sure what happened to Joe. Only one thing is certain. Joe had a sense of history. He escaped April 21,1837, on the first anniversary of the Battle of San Jacinto----a battle that gained Texas its freedom.

Originally published in True West Magazine, February 1998

edition. Used with Permission. Illustrations by Gary

Zaboly.

Alamo Graphic by Randell Tarin

The Second Flying Company of Alamo de Parras, ©1996-1998, Randell Tarin. All Rights Reserved.